Machine gun fire clattered in the distance. Under a charcoal sky, the forward position was hotly contested by enemy forces, and bullets scattered over the muddy, bomb-scarred terrain. One soldier nestled into a crater with his rifle resting beside him. While his squadmates laid down a suppressing fire, he tore a velcro pocket open and pulled out his rations, a rectangular brick wrapped in tinfoil. He winced, tentatively tearing the foil to reveal a beige opaque block. The soldier gripped the upper corner and broke a piece off, granules crumbling on his khaki body armour. At the top of the crater, another soldier was wrestling with the recoil of his massive M60. He looked to his ally beside him, saw the ration pack and stopped firing.

‘Godspeed,’ he said, saluting his brave comrade before resuming his fire.

The soldier placed the broken beige wedge into his mouth and cringed. Three chews were all he could manage before spitting the dusty rations out. Gagging, he tossed the foiled package away, picked up his rifle, and prepared to vacate the crater to charge the enemy. He sprung up, and the soldier sprinted through a hail of gunfire. Then he slowed. And then fell to his knees. Malnourished, he perished under an oppressive, empty stomach. And the villains triumphed, and evil spread, and all goodness was in jeopardy.

At least, this was the fear of the US military. Throughout the twentieth century, rations (or MREs – Meal-Ready-to-Eat – in military jargon) were growing more sophisticated in nutritional density to ensure soldiers would get everything they needed to continue their high levels of physical exertion; well, sophisticated in every way aside from taste.

By the 1970s, the US military was in the thick of the Cold War, a global conflict that saw over half a million soldiers deployed in Vietnam alone. As the Cold War progressed, the US military learned that most soldiers were eating only half of their MREs, leading to a growing concern that soldiers would be too weak to win wars. So, in 1971, the US military hired food behavioural scientists to address this problem. One such scientist was the infamous Howard Moskowitz, one of the biggest influences in the modern food industry.

Moskowitz was a Harvard-based Psychologist and Market Researcher. A passionate eater, he developed a system that quantified taste. Moskowitz created mixtures with varying degrees of sweetness, saltiness, bitterness and other flavours. Then, he gathered test subjects around the Harvard campus by paying students 50 cents to taste these mixtures and rank them from favourite to least favourite. While it might now be considered an elementary study, there was so little science behind eating behaviours at that point that Moskowitz’s work gained him some repute. Shortly after graduating, he was drafted to work with the US military. [Moss, 2013.]

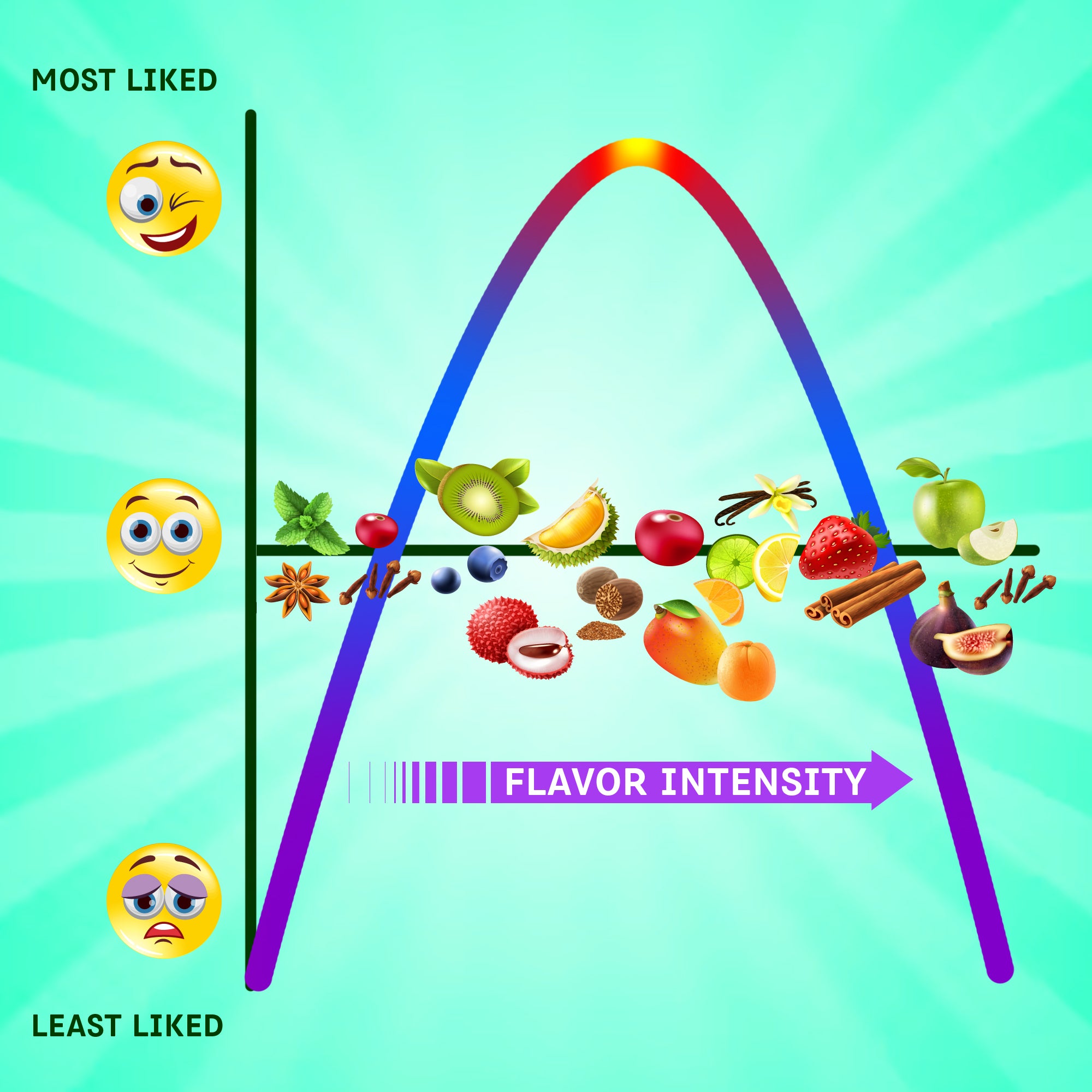

He started working in research labs in Natwick, a town sixteen miles outside Cambridge. While other food scientists attempted to refine the MREs, Moskowitz gathered data from the soldiers themselves, mirroring the system he created at Harvard. He asked the soldiers their favourite foods, particularly those they could eat the most of. An interesting pattern emerged: one’s favourite food and the foods they ate the most were rarely the same. Many people’s favourite foods are rich in specific flavours, making every bite a more profound sensory experience than common snacking. With these experiences, however, we tend to feel more full, whereas traditional snacking foods, despite often having higher caloric content, would not have this effect. This is known as ‘sensory-specific satiety,’ big flavours that overwhelm the brain and create a ‘full’ feeling in the body. This revelation – more flavour = more full – became Moskowitz’s north star, and he set out to create a perfectly balanced flavour profile of MREs that was flavourful enough that the rations were easy, even enjoyable, to eat, while not too flavourful in any one way that they triggered sensory-specific satiety. From this, the pursuit of the Bliss Point was born.

The Bliss Point

Before being commonly used within the food manufacturing industry, the Bliss Point existed within math and economics as a 'sweet spot' for something at the top section of a bell curve, where quality and quantity were balanced in a way that didn't diminish the worth of either. Within food, it is a formula of flavour profile where a food is as tasty - sweet, salty, etc - as possible without being overpowering. The most successful processed foods tend to have the most optimised bliss points.

In his astounding book Salt, Sugar, Fat, Pulitzer-winning journalist Michael Moss gives an overview of the processed food industry from the perspective of those titular three pillar nutrients, the same three that food manufacturers wield to create their bliss points. Every food manufacturer has different methodologies, but they are not unlike Moskowitz's Harvard system. When designing a new product or modifying an existing one, manufacturers will create countless versions with varying degrees of sweetness, bitterness, saltiness and mouthfeel. Then, they narrow down the most popular products and hone in on their bliss points. When that is established, they calculate the ingredients used to achieve those bliss points and then decrease their usage where they can while still retaining the product's bliss point (remember, despite the name, the bliss point is the top portion of the bell curve, not its peak.) This back-and-forth, the experimentation with ingredients and chemicals to perfect the taste, maximise shelf-life, and reduce costs, is the alchemy that creates the scroll-length lists of ingredients at the back of processed food packaging.

Julie Mennella, a biopsychologist, theorises that our individual bliss points are formed in our childhood, a time when we are particularly vulnerable to the advertising of junk food manufacturers that shape our sweet tooths. Moskowitz was among the first to understand the market opportunity of these diverse bliss points. Before Moskowitz's innovation, for example, there was only instant coffee; when he started working with Maxwell House, the singular instant coffee became a trio: Mild, Medium, and Dark, with each version hitting a more nuanced bliss point.

This is Moskowitz's legacy: the widespread pursuit of bliss points within processed food, a legacy that Malcolm Gladwell said 'fundamentally changed the way the food industry thinks about making you happy.'

The Three Pillars

Salt, sugar and fat play different roles in how and what we taste. The push and pull between these three create the bulk of our palate and cravings.

Of the three, Salt is the most elusive in why we crave it. Salt is a terrific tool for its ability to enhance flavours, elevate sweetness and dull bitterness, and its rarity in pre-historic times, paired with our need for sodium, likely influenced our cravings for saltier foods. Sodium is the primary chemical component of Salt – or Sodium Chloride as it is scientifically called – and the human body needs it to regulate water levels for cellular osmosis, muscle and nerve functions, and electrolyte balance.

Some studies suggest that, despite our necessity for sodium, Salt is a flavour we’ve learned to love rather than something we inherently crave, which differs from the likes of sugar. One study detailed in Moss’ book conducted by Monell Chemical Senses Center illustrates this in children:

To test the kids' fondness for salt, the Monell investigators, led by Leslie Stein, gave them solutions of varying salinity to sip, starting when they were two months old. At that age, all the kids either rejected the salty solutions or were indifferent to them. At six months, however, when they were tested again, the kids split into two groups. Those who had been given fruit and vegetables to eat still preferred plain water to the salty solutions. But those who had been fed foods that were salty now liked the salty solutions. Over time, the two groups- the salted and the unsalted - grew even more disparate […]

When the study was released, Gary Beauchamp, the centre's director and a co-author, talked about its significance. These were kids being studied, he stressed. Kids who were not born liking salt. They have to be taught to like the taste of salt, and when they are, salt has a deep and lasting effect on their eating habits[…]

With this revelation, the industry's heavy use of salt moves from the realm of merely satisfying America's craving for salt to creating a craving where none exists.

[Moss; 2013; Pg. 279-280]

The rise of cardiovascular and blood pressure problems coincided with the increased use of salt in processed food and its consumption. While other factors certainly contribute to the holistic nature of poor health, conducted studies throughout the years continued to point at salt as a significant contributor, and as a result, food manufacturers experimented with additives to substitute it with; one such was potassium chloride. Despite the substitutes, which have never been able to replace salt completely, sodium chloride remains a pernicious presence in processed foods.

Sweetness and Sugar are synonymous, and sweetness is likely the first flavour you learned to love as a child. It may not surprise you that Sugar is often the ingredient most linked to food addiction. Considering that Sugar is calorie-dense and, therefore, more desirable to sustain our bodies in times of scarcity, our primitive bodies came to know sugary foods as nutritional jackpots. Sugars are a primary energy source for the body, both for immediate and delayed expenditure and contribute to normal brain function and cellular respiration, a process that has cells expending energy to perform various functions.

Like salt, Sugar has evolved as an ingredient in multiple forms, and higher and higher levels have been smuggled into our processed foods. Initially, food manufacturers championed using Sugar as a magic bullet to improve the taste of their foods, but with growing awareness of various health crises, they had to pivot. One such pivot was the marketability of fruit and the healthy connotations attached. Most notably and most common today are juices made from concentrate - essentially a condensed form of the fruit’s Sugar – or advertising claims of using ‘real’ fruit when the ratio skews dramatically toward additives. Another pivot was using sugary alternatives such as fructose or glucose syrup or artificial sweeteners that substitute Sugar entirely and carry their own health risks.

As Moss describes, Fat has no intrinsic taste but rather a ‘gooey, sticky mouthfeel’. Fat is predominantly experienced within a nerve called the trigeminal, which is used to distinguish texture. While reduced fat content can be obscured, it often lacks a full-bodied feeling in the eating experience. Despite this, Fat can be the most pernicious of these three pillars because it is often the one our bodies are the least perceptive to. Too sugary and too salty are easy markers, whereas it takes something exceptionally fatty to trigger our distaste. Moss details a study that illustrates this:

In 2008, a team of Dutch researchers conducted an experiment to see whether people will eat more or less, depending on whether they can easily see the fat in their food.

"The products we used were foods that are commonly consumed in the Netherlands, but we manipulated them in order to create a visible- or hidden-fat version," the team leader, Mirte Viskaalvan Dongen, told me.

Tomato soup was served with a vegetable oil slick floating on top and then, in the hidden-fat condition, with the oil emulsified into the soup. Bread was served with butter spread on top of the slices, so it was visible, and, alternatively, baked into the loaves, so it was not.

"We also used a small bun with a sausage inside," he said. "I am not sure whether these are available in the U.S., but in the Netherlands they are quite common. In the visible-fat condition, the bun was made of puff pastry, which has a very fatty appearance. It is shiny, and when you hold it in your hand, you get greasy fingers. In the hidden condition, the bun was made of dough that does not have the fatty appearance."

[…] The results were striking. The participants were first asked to estimate the amount of fat and calories in the food, and in the versions where the fat had been tucked away, they sharply underestimated the levels of both. Next, they dined on the foods, having been told to eat as much as they wanted. The visible fat group got fuller faster, while the other group, downing the hidden-fat recipes, remained hungry and kept eating.

In a key — but commonly overlooked — aspect of obesity, weight gain can be caused by the slightest increases in consumption, if it continues day in and day out.

A mere extra one hundred calories a day will, over time, put on the pounds. The participants in the Dutch study hit that mark exactly. When they couldn't see the fat in their food, they ate nearly 10 percent more or about 100 extra calories.

[Moss; 2013; Pg. 180-181]

Fat is also the component with the highest proportion of calories, which means our bodies have evolved to greet fatty foods as essential allies in the fight against hunger. It is also used to store energy within the body for times of scarcity and to assist cognitive function, hormonal regulation, and vitamin absorption. Nutritionally, fat is also a minefield. As stated, it is calorie-dense and crucial, but, as has been said to death in the zeitgeist by now, not all fat is good. Even the simplest foods tend to comprise different types of fats distinguished by their chemical structure, all of varying use and harm to us, so discernment and moderation are key.

Contemporary Bliss: Follow Your Dopamine

What's not covered above but is present in all three components is their role in our internal reward systems. Foods that are high in one or all of the above trigger our dopamine circuitry, which encourages reward-seeking patterns, which can lead to addiction when indulged in excess over time. Junk food is appealing because it marries our behavioural love of convenience with the faux promise of nutritional wholeness and our neurological pursuit of reward. Along with marketing and the seeming ubiquity of processed food, reaching for junk food often feels like it makes us whole.

For anyone interested in cutting down on junk food consumption, I'd encourage you to read Michael Moss' Salt, Sugar, Fat. It pulls your eyes open not just to how unhealthy processed food can be but also to how ugly and sinister it is when stripped away from the pretty packaging and marketing campaigns. It's a profound lesson that indulging in food when we don't necessarily want to is often shaped by biology and decades and trillions of dollars worth of industry influence. We are engineered to get the most out of food, and food is engineered in kind.