A genre was born in England, 1859. A rosy-cheeked, mutton-chopped and cantankerous-looking man named Samuel Smiles wrote a book that became a cornerstone of one of modernity’s largest industries. Disillusioned with failed pursuits in medicine and journalism, Smiles turned his intellectual and literary talents inward and wrote the seminal book Self-Help. While this book had problematic rhetoric - simplifying poverty as merely a problem of poor personal habits, as an example - it preached the virtues of self-reliance and perseverance in a manner so resonating that this 300-odd page manuscript made Smiles an overnight celebrity. As of 2022, the self-help genre is estimated to be worth $43 billion and has splintered into every subject you can think of. Yet the proverbial buck hasn’t stopped at these airport paperbacks.

If you look around at any major medium or media platforms, it’s difficult to get away from an air of hyper-optimisation; better and more are always the goals. And while fables, metaphors and even religions all warn of this too-human sense of inherent dissatisfaction, it is strange to find ourselves in a place where we actively cultivate a culture of ‘fixing’ or pursuing abundance to remedy that mortal dissatisfaction. Why is this relevant? Because this culture of optimisation is influencing industries and habits that on the surface seem to be antithetical to optimisation, one major one being the well-earned vacation that now often comes in the form of a wellness retreat.

For perspective, the Self-Help genre grew to $13 billion since its infancy in the late nineteenth century. Wellness Tourism - becoming popular in the late twentieth century - is valued at $814 billion as of 2022, but is estimated to rise to $2.1 Trillion by 2030. Admittedly, these figures are apples and oranges - Wellness Tourism costs so much because its products usually encompass the entirety of a vacation - but given that Wellness Tourism is one of the fastest-growing markets in the world, it's worth questioning why are so many people willing to pay so much for the pursuit of wellness, and why is this trend happening in the first place?

A Lens of Leisure

“Amusement under late capitalism is the prolongation of work. It is sought after as an escape from the mechanized work process, and to recruit strength in order to be able to cope with it again. But at the same time mechanization has such a power over a man's leisure and happiness, and so profoundly determines the manufacture of amusement goods, that his experiences are inevitably afterimages of the work process itself."

- Theodor. W Adorno & Max Horkheimer, The Culture Industry, 1944.

I first came across Adorno when I did a post-graduate diploma in English. I had just returned from spending a month in a Buddhist monastery in Nepal – I can feel your eyes roll at this, but trust me, it’s not the swashbuckling humblebrag you might think. I spent most of my time in the monastery teaching English to young Buddhist acolytes whose ages ranged from toddlers to teenagers. I had occasionally spent lengthy periods in deep meditation and learning about Buddhism from the more bonafide always-in-lotus-position-type monks, but it was mostly a pleasantly mundane time among pleasant people. No real epiphanies or spiritual awakenings to speak of.

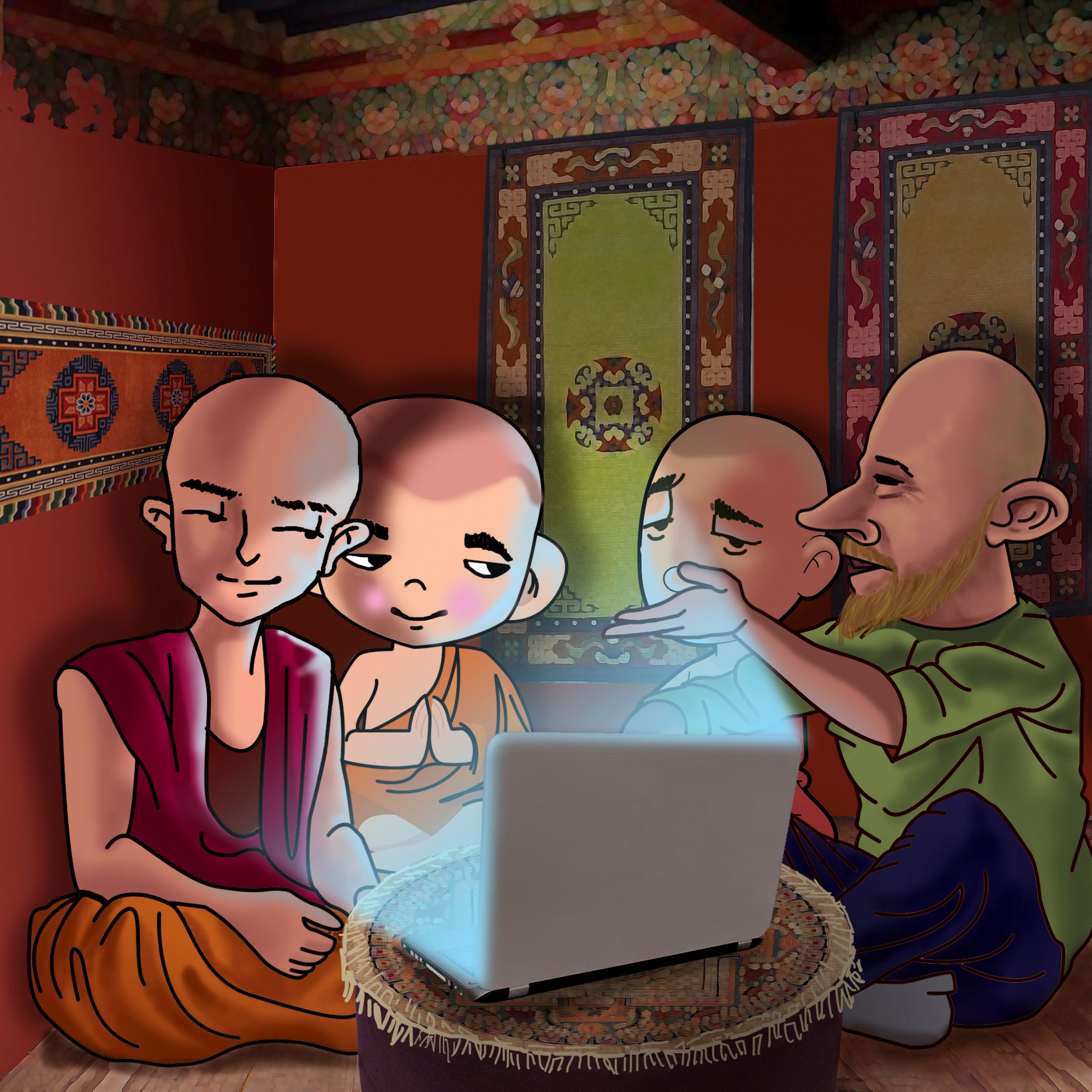

It was so mundane that probably my most treasured memory to speak of came from using my bricky laptop to show a group of monks a particularly dull episode of Twin Peaks. They gathered around in my room - little more than a square of stacked cylinder blocks insulated with carpets stuck to the walls - and with curious frowns they nodded along to me while I tried to explain the premise of this bizarre TV show to them.

With that enlightened aura that suggested he was always on the brink of laughter, one monk asked me 'And they watch this where you’re from?'

‘Some people,’ I said.

And he only nodded in return, content that I had proven he was missing absolutely nothing outside of his ascetic life.

After the trip, I returned to Ireland to study English and become a teacher. The above context is to illustrate that I was not only a little wayward then but had also just had an experience that made me fundamentally question how I spent my time. Not that I'm a believer in squeezing personal growth out of everything, but that whole month seemed eclipsed by the fact that my greatest anecdote spent with some of the most radiant and wise people I’ve ever met was half-justifying my slog through season two of Twin Peaks. So when I read that above Adorno quote in my English course – which was predominantly focused on capitalism’s influence on the commodification of art – my recent experience slotted the philosophy into the context of ‘spare time’ in general, how one decides to achieve and maximise – or not – that spare time, and what’s motivating that pursuit of achievement and maximisation? To bring it back into the context of wellness, I’ll rewrite the quote:

“The pursuit of wellness under late capitalism is the prolongation of work. It is sought after as an escape from the mechanized work process, and to recruit strength in order to be able to cope with it again. But at the same time the work process has such a power over a man's leisure and happiness, and so profoundly determines the pursuit of wellness, that his experiences are inevitably afterimages of the work process itself."

In short, this cornerstone experience informed a period in my life where I wasn’t against any kind of proverbial ‘hustle,’ but had become very conscientious about my spare time and the validity of my leisure, and how even within that conscientiousness – in this case pursuing wellness – there could be something faulty about the approach.

Wellness

It’s fair to say that the want to be well is a universal feeling, it neighbours the compulsion to survive. Practising wellness and self-improvement are virtues, yet modernity has seen this basic pursuit evolve into a far more consuming beast. The reasons for this vary, though most are obvious considering how far society has grown.

One of the main contributors to this evolution is humanity's extended life expectancy and a growing mindfulness towards healthier ageing. Technology has also advanced, providing tools that facilitate better self-care, not least of which is the internet and social media, providing much greater access to information that can educate individuals toward healthier habits. Medicine has moved towards preventative and not solely reactive, and globalisation has provided access to a wealth of different cultures and holistic ways of living.

The less-than-sexy contributor to the wellness boom is the gaudy reality of growing affluence in certain societies. Pursuing wellness isn’t solely a privileged pursuit, but it is more common and the means with which you pursue it are more accessible if you have the money. This is especially the case in wellness tourism. In 2013, the Global Business Travel Association published the “European Business Traveller Well-being Study,” and according to those decade-old statistics, 'Wellness Travellers' paid on average 130% and 150% more than the average tourist in global and domestic contexts, respectively. The expense differences ranged from access to products within the wellness umbrella such as gym facilities, healthier meals, and room upgrades. Regarding room upgrades, reasonable features such as the blackout curtains were common – I too am a diva for sleep – but also seemingly silly things such as Vitamin-C-infused showers, which after doing a little bit of research, definitely betrays notions of superficial wellness rather than science-backed health benefits. But the macro-level of this trend goes far beyond paying for perks, the pursuing spirit often dictates the entire trip, a strange thing considering that, in my mind, there has never been a greater anthesis to work than vacation.

Vacation

Vacations – and more broadly free time – have existed since ancient times, but the packaged allotment of time to a distant destination might very well have its roots in religious pilgrimages. Then the 18th century rolled around and European societies started to deem it valuable that their youngsters travel for a medium-to-long period and soak up neighbouring cultures. Back then this was called a grand tour, though it still exists today and is usually referred to as a gap year by us anglophones. Yet the opportunities to visit the Holy Land or broaden your horizons over a meandering stint on the continent were not available to everyone, but rather a small minority. And this was not solely a fiscal restraint, labour laws and worker rights are a relatively recent development. Even outside of extreme circumstances such as slavery, the right to simply not work and faff about on your own time was not a given. But the mid-twentieth century saw Labour movements advocate for and achieve these legal rights to relaxation, just in time for the growing trend of pre-packaged tourism.

Mass tourism grew rapidly with the development of transport and packaged tourism likely grew in conjunction with that and the rapidly expanding advertising industry, as well as the economic prosperity that spread in the west following World War Two. Approaching the 21st century, with the growing societal factors outlined earlier, a wellness-orientated variety of packaged tourism became inevitable.

Wellness Tourism

The Global Wellness Institute defines Wellness Tourism as ‘travel associated with the pursuit of maintaining or enhancing one's personal well-being,’ usually via physically, mentally or spiritually rejuvenating experiences. Modern examples of this – most of which are tellingly named ‘retreats’ – consist of yoga regimes, detox programs, meditation courses, and culinary classes, all the while taking place in an idyllic location far from home, ideally somewhere authentically related to the relative retreat – think a yoga retreat in its birthplace of India. The Wellness Tourism label can also be applied to practices or experiences within a trip that don’t necessarily define the trip's ethos or totality – enter Vitamin-C-infused showers.

Fitt Insider wrote an illuminating article that heavily informed this one, and I'll summarise their list of positives and negatives within the Wellness Tourism industry below. One major benefit of Wellness Tourism is the same for any form of tourism: an economic boost for destinations, especially considering the aforementioned statistic of wellness travellers willing to spend 130% more on their trips. Another major benefit is that these types of trips seem to genuinely improve one's wellbeing.

One study examined a control group during and after attending a 1-week wellness retreat in Queensland Australia. The retreat consisted of leisurely and educational activities while consuming an organic and mostly plant-based diet. The study used multiple metrics to measure the well-being of the attendees immediately and six weeks after the retreat, which included self-efficacy questionnaires, depression and anxiety scales, insomnia scales, and biometric tests on urinary pesticide metabolites within each subject. The results showed that at least some improvements were seen in every department and persisted beyond the six-week window. However, there was a notable flaw in that study. The chosen participants were selected from a group that had already attended at least one of these retreats prior. Based on that, we can assume that these people held and acted on the values of prioritising personal wellness and likely practised other means of self-care outside of the retreat and the study. In short, how well can you rank the efficacy of a wellness retreat if you’re measuring people who likely already practice wellness in their day-to-day?

In fairness, those broad strokes do a disservice to the study – the results, after all, genuinely look favourably on the retreat - but considering the low amount of studies on this industry, it might behove a little suspicion, because scepticism is warranted. One such way is that the wellness industry in general lacks any regulatory authority, meaning no minimum standard is maintained or enforced from retreat to retreat. In cases where a retreat cuts corners or provides a fraudulent product, the best an eager traveller can hope for is merely a lesser experience, the worst case being tragic deaths caused by negligence, which have happened. Ayahuasca retreats, as an example, where travellers seek to ingest the hallucinogenic brew in the pursuit of drug-fueled revelations, have their fair share of casualties. However, a 2020 media review of the reported ayahuasca-related deaths of 58 people revealed that not one of the autopsies stated that the deaths were caused by acute ayahuasca intoxication, meaning that the setting and governance played a large if not total role in these deaths. The review concluded:

‘In the few cases where ayahuasca did play a part, the majority of deaths could have been prevented if the experiences had adhered to the minimum safety standards.’

While ayahuasca is certainly on the extreme side of wellness, it illustrates a frightening point that corners are even cut in situations that are high risk.

Another alarming trend related to regulation is infrastructures - or lack thereof - within wellness retreats, usually related to their inability to handle large influxes of people, the cost of which often comes at the expense of the local ecosystems. Waste disposal has often been cited as a massive problem, with countless accounts of ashrams or hotels dumping unprocessed human waste into local rivers. The sliver of silver lining here however is that the demographic that typically seeks wellness travel are also the same ones who prioritise eco-friendliness, and so their values are dictating positive change in this regard and will likely continue to do so. The question, along with many things regarding the environment, is how fast can these changes come?

The Demographic

You might wonder who are these zen-seekers informing the wellness trends. Millennials - you might not be surprised to learn - are the main demographic behind the explosion in wellness tourism. The millennial/self-care alignment likely happened because they were the first generation to come of age alongside the internet. More than ever before, millennials had wide access to content during key formative years, content that provided insight, data and tools that not only inspired change but communicated practical methods and frameworks to follow through on those inspirations. While much of this information might have traditionally been communicated by teachers or family members to lesser degrees, the internet provided a degree more agency to the individual as this wellness-related information was either stumbled upon or actively sought. Yet, the double-edged nature of this information is worth acknowledging. These tools may also perpetuate and even exacerbate the insatiable dissatisfaction of human nature, creating a cycle of self-examining flaws, finding solutions to remedy flaws, the solutions ultimately not quite bringing satisfaction, self-examining that dissatisfaction, pursuing solutions, and so on.

The millennial generation will continue to grow into and occupy the majority of wealth, and so the wellness pursuit and its tourism products will grow along with it. But the question remains, what kind of growth is this? The cynical view is that millennials have either been tricked or have slipped on a banana peel and fallen into a harmful pattern of trying to maximise every element of our life, a life’s emphasis on pursuing rather than being. The optimistic view is that we have started to learn to be conscientious enough to know what is and isn’t nourishing us, and have decided to live – and travel – accordingly. Time will tell which, if either, is true and whether these patterns will elevate or diminish us.