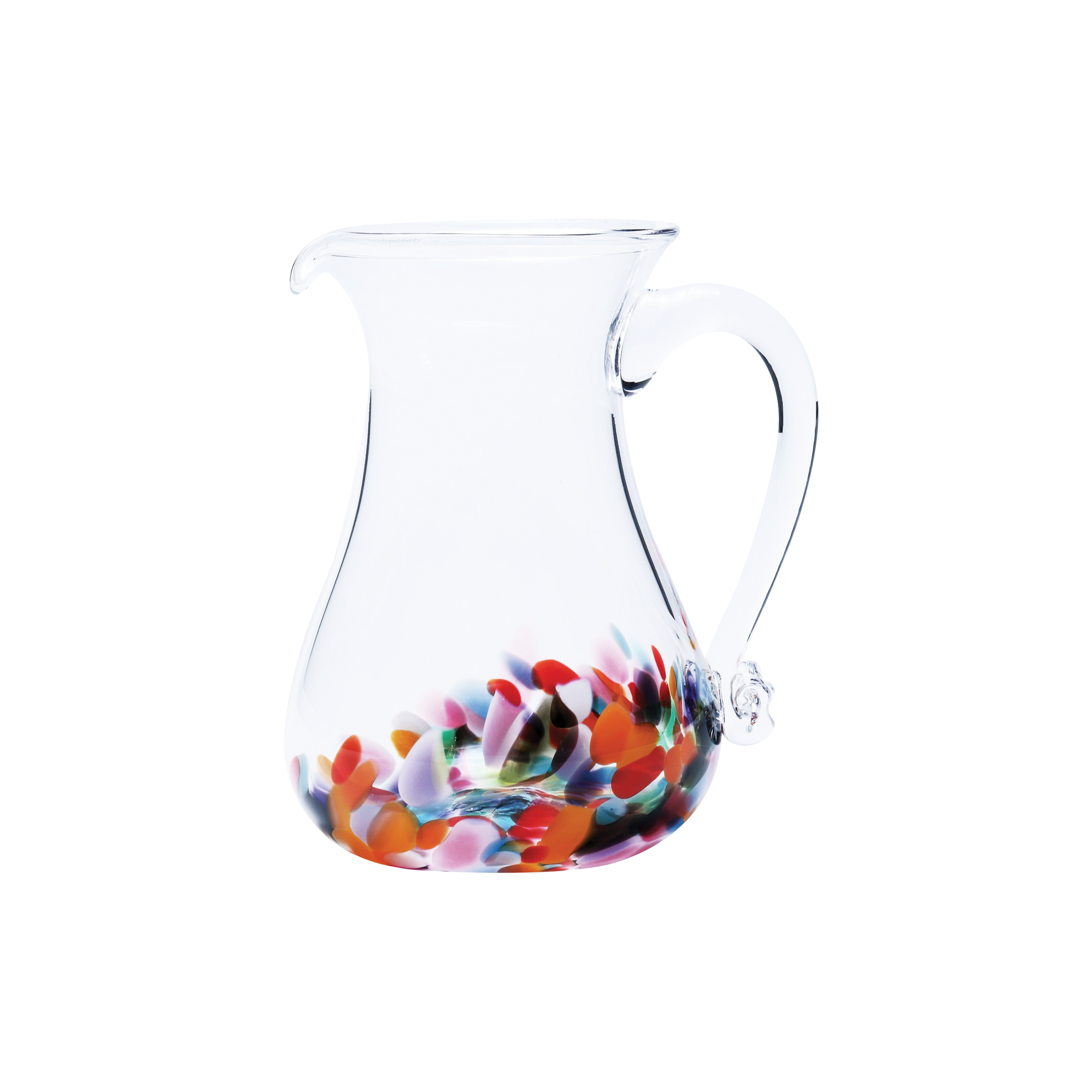

Jerpoint Glass Studio in Kilkenny have built a reputation for producing vividly imaginative pieces of glass magic that tell a story all their own. But from where does the artistry of glassblowing originate, and how has the process for producing such magnificent sculpts changed over time?

History of Glassblowing

The natural elements that contribute to alchemical glassblowing are as old as the sun and the stars; extreme heat, especial stone, and above all else, patience, which sees to the creation of a material that can be as delicate as woven silk or robust as armoured plates.

The first glass created by man is thought to have come from Phoenician sailors. The ancient Roman historian Pliny suggested that it was an accidental discovery, brought about when the shipwrecked sailors thought to build a fire atop a bed of sand, using blocks of soda to bolster their cooking pots. The fire they made raged through the night and when the sailors awoke in the morning they discovered that where the heat had come into contact with the blocks of soda and bed of sand that glass had formed in their place. The combination of heat, sand, and stone had proved the perfect concoction for man made glass, the likes of which had never been seen before.

Well, perhaps not – as it is also theorized that manmade glass first originated in ancient Mesopotamia, when potters from the region discovered the material firing their wares. The belief here is that while these potters had been firing their wares, testing out materials that were aesthetically pleasing and durable too, they stumbled upon the discovery of glass, leading to the expansion of glassmaking methods in the process. This theory is backed up by the fact that the oldest fragments of glass have been found in the Mesopotamian region, the skill during this time mainly reserved for producing vessels, although some jewellery did still exist. The jewellery, consisting of small beads and amulets, were exclusive to high priests, pharaohs and nobles, and it wouldn’t be until the arrival of the ancient Roman Empire that glass workshops truly had their day in the sun.

The glass industry expanded in tow with the ancient Roman empire, the civilization’s conquests, trade relations, infrastructure, and emphasis on architectural beauty providing the perfect platform for the craft to develop and sophisticate. The time of Emperor Augustus saw glass objects spring up in Italy, France, Germany, Switzerland, the sought after material even making it as far as China, travelling along the silk road. The applications of glass during this time also changed, transforming from a material predominantly used for jewellery and vessels and becoming instead the centrepiece for architectural pursuits. The introduction of manganese oxide to liquid glass compounds intended for later moulding managed to produce a clearer glass that could adorn the outside of buildings and forums, the inability to see through said glass a lesser misgiving when compared to the elation of its aesthetic affect.

Glass production at the height of the ancient Roman Empire witnessed more craftspeople settling into select areas and migrating less. The East, and more specifically, Alexandria, was renowned for its ornate expressions of design whilst the Western more Germanic regions did not find their calling until the cessation of the Roman Empire. It was then, when the Empire collapsed, that the West began to focus less on ornamentation and more on functional glasswork. This focus on functionality led to the creation of sheet glass, the long, slim, glass panes becoming successors to the clouded creations that adorned the outside of Roman forums and their chosen buildings. The method for producing such glass was relatively simple, as craftspeople would blow a hollow sphere of malleable glass and swing it vertically, allowing gravity to pull the glass into the shape of a long cylinder. From here, the craftspeople would cut the cylinder down its centre and flatten out the two separate pieces, resulting in glass sheets. These methods, initiated by Germanic craftspeople would later inform the Venetian glass crafters of the 13th Century and pave the way for paned windows and stained glass later on.

The Dark Ages in Europe would see a lull in glassmaking that was later rectified during the Middle Ages when the Catholic church rose to prominence. Glassmaking and innovations in the field of glassmaking during this time revolved around stained glass, and the ability of glassmakers to display biblical stories and images inside the material itself. The Middle Ages also bore witness to the fall of the Islamic Empire and where once the trade routes belonged to the East they now started to establish themselves on mainland Europe, the central hub of which was located in Venice.

The importance of Venice to world trade in the 13th Century meant that countless tradespeople, craftspeople, and merchants settled in the city to reap the rewards of improved infrastructure. This melting pot of activity brought about an abundance of organized artisans and in the early 1200’s, the Venetian Glassmaker’s Guild came to be.

The story of glassmakers in Venice is something of an oddity, as towards the end of the 13th Century it was declared that all glassmakers from centre would need to relocate to the island of Murano for fear that their excessively hot ovens would see the city set alight. This justification for shifting an entire trade might seem plausible when one considers the Great Fire of London that occurred three centuries later but when compared to previous declarations made in Venice regarding the trade of glassmaking, this exile paints a different picture. It was twenty years prior to the exile of Venetian glassmakers that Venetian lawmakers decided that foreign workers were expressly forbidden from joining the Venetian Glassmakers Guild. This law, coupled with the exile that occurred twenty years later, has caused many to believe that the exile was enforced so that Venice could shield its glassmaking secrets. More to the point, it is said that those same artisans and their families located on the island of Murano, an hours gondola ride away from Venice, were not allowed to leave the island for fear of incurring the penalty of death. The glass industry on Murano was strictly controlled but this doesn’t mean that some daring glassmakers didn’t find means of escape, fleeing from the island and bringing their knowledge to France, Flanders, and England. During this time, Venetian glass was celebrated for its exceptional quality, with new varieties of the material such a cristallo becoming renowned for its clarity and the colours that were infused within the delicate wares sought after by all. It was also during this time that there were major innovations in the way that mirrors were produced, as no longer did one need to seek their reflections upon a piece of polished metal and instead could enjoy their countenance upon meticulously clear glass, lined at the back with foil and perfected to possess the sharpest of images.

The secrets to glassmaking wouldn’t see the light of day until the seventeenth century, when a book called ‘The Art of Glass’ was published by the well-travelled and extensively trained alchemist, Antonio Neri. Neri’s musings on the craft of glassmaking covered everything from the making of glass, to the construction of glassmaking equipment, and even detailed the proper techniques for blowing glass too. The book came at a time when greater transparency was descending on the craft of glassmaking, and although Venice still had a firm grip as industry leaders, other European countries were beginning to gain speed. In England, Spain, France, and Germany new kinds of glassmaking houses were beginning to emerge, known as forest glasshouses. These houses, as would become the norm later on, began experimenting with materials that were abundant to their surroundings. In the case of the forest glass houses, the main ingredient for their glass came from ashes of wood that had been burned to heat their furnaces. These ashes were purified and mixed with copper oxide, and produced a dark green glass that was perfect for storing beverages. This theme of taking unusual ingredients and finding new ways of producing glass saw to innovations that propelled the artistry of glassblowing forwards. Chalk based glass created in Bohemian glasshouses proved to be soft and supple enough for diamond engraving, whilst led based glass created on English shores stayed malleable long enough to fashion fresh forms and exciting designs that beforehand wouldn’t have been possible. The clarity and quality of this led based glass, along with its ability to be interpreted in imaginative ways saw to the lessening of Venetian controls over the glass industry and the beginning of global marketplace, where the playing field had finally been levelled.

The nineteenth century saw this global marketplace begin to cater to a growing middle class. The Biedermeier style of aesthetics and living perpetuated an idea of minimalism, one that capitalized on the nesting instinct and championed unassuming wares. The materials people used to adorn their homes were in direct contrast to the flamboyant French style of architecture that had defined the Romantic period and unassuming, inoffensive design became the norm. The glass pieces produced during this time were stalwart and almost kitsch in the manner that they skirted excess but strived for individuality. It was not uncommon to find a plain drinking glass ‘elevated’ with an enamel painting of a fish in search of water or gold trim wrapped around an otherwise undecorated jug.

These limitations, although not unusual for the tastes of the time, were also thanks to excise duties that existed on glass, particularly glass entering Britain, and it wouldn’t be until the midpoint of the nineteenth century that these additional fees were lifted. This lifting of fees opened up the possibility of glass being used not only in a functional capacity but also impressive artistic pursuits. The World Fair of 1851 held in London hosted a gargantuan glass building known as the Crystal Palace that housed wares from around the world, the oddities and treasures inside the Palace overshadowed by the venue itself. This perception of glass as high art and its ability to become a behemoth of craft revived Bohemian and Renaissance interpretations of the material, leading glass to be found in more homes, not in the half-kitsch, half-classical style it had been before, but as it was intended, clean and simple.

This growing demand for simple wares in grand quantities would coincide with art movements of the nineteenth century that saw the material presented under a new light. The World Fair had played its role in showing that glass could be used for more than sheer functionality and the emergence of the Art Nouveau movement at the end of the nineteenth century saw glass separate itself from an identity indebted to industrialism. Glass had become something other than harbinger of light to dull homes and the Nouveau style of glassmaking wished to distinguish the material from fine art too. This meant an ambitious recontextualization of glass under the monikers of nature, and movement, elegance, and flow. The French glass artists, such as Emile Gallé, strived to create pieces inspired by nature, with vivid colours and affecting tones that elicited memories of botanica and insects, the Portland Vase, and Japonisme masterpieces. This commitment to natural themes also travelled to the United States, where Louis Comfort Tiffany spearheaded the Nouveau movement. Tiffany had an affinity for Roman glass pieces and their opalescence. This iridescent effect later adopted by the artist was not the result of human interference but the passage of time, as over course of some centuries the weathering of glass buried under ground caused thin layers to separate and flake, leading to the incredible refraction of light between the layers. This glittering effect would go on to characterize much of the artist’s naturalistic work, even earning him a grand prize at the Paris Exposition (World Fair) of 1900.

The end of Art Nouveau sometime into the twentieth century would allow for the introduction of a new style, known as Art Deco, characterized and influenced by the growing fascination with technology in modern society.

This growing fascination and infatuation with technology in modern society has remained prominent in the world of glass. So much so that the twin attributes for which the material was previously renowned are now inseparable from one another; form and function existing as one. We see it in our smartphones and televisions, the electronic screens that flood our public transport; sleeker, slimmer, shinier more responsive, and more elegant. It’s to the point that we can no longer appreciate the craft that goes into producing these wares, the artistry second to the application. And it’s something of a pity that cannot celebrate this alchemical material for its natural beauty anymore, as something that stands apart from all else. Our fast paced lives and even more fleeting appreciation for things has made us scrutinous in the worst possible way; how will it benefit me, what does it do, how does it work, what is its worth?

Perhaps it’s time we get back to appreciating true artistry, where the imagination, finesse and care that goes into our wares is the foremost reason we cherish them and the constant scrutinization of a consumer society takes a backseat.

Whether it be an ornate piece that adorns the mantlepiece or a collection of glassware from which we toast grand milestones; take a breath, enjoy good company, and cherish special moments made all the more memorable with one of a kind artistry.